In my youth, I was brought up with nature all around me. Aside from the music, TV and film that adorned my family home, my uncle played a pivotal role on the way I connect to the outdoors. Spending hours scurrying over the Hawkstone woodland in Shropshire, watching the fields role by, listening to the breathing steam engine on the Severn Valley, or just venturing to RSPB reserves was a common occurrence for little-me.

In the early 90s, the BBC aired a program that would become the basis for some of my own investigations. The program was called ‘Daylight Robbery’, it involved watching squirrels run obstacle courses, with their ultimate goal to reach the food at the end. This gave me the inspiration to test the birds that visited my garden every year. I would create small, but elaborate puzzles for the birds to try, all in order to attain a nutty treat for their troubles. These were made from a mix of standard and Technic Lego, allowing me to create some great machines, at a low cost to myself.

Bringing you up to 2017, I recently viewed a new experiment on BBC’s Autumn-Watch, where they were testing the learning capabilities of foxes. Again, they have inspired me to rekindle the old puzzle idea, allowing me to show my 6 year old some of my old tricks, and involve her in some ‘living-world’ science. It is the birth of ‘Project Bird-Brain’. The aim is simple, taking the old ideas, and bringing them to now, I want to test the garden birds, questioning their ability to learn and adapt. The questions that I am ultimately attempting to answer are:

- Can our garden birds learn to achieve a goal based on an increasing set of levelled tasks?

- Are there any notable correlations within the data?

- Which bird shows the most able to learn and/or adjust to the task at hand?

At this point, the questions are pliable and not set in stone, although they will not deviate from their desired outcomes.

Science has speculated the intelligence of birds for years. The crow is often observed, used as the basis for many tests, they have been given a ‘monkey’ like status. Some species of bird are seen using tactics for survival, or creating simple ways to benefit their day-to-day lives. It is not the general intelligence that we are looking for, here, but the overall adaptability of our garden visitors. Had I made recordings from my younger-self’s investigation, I would love to have answered a fourth question: Has there been a change in adaptability in the past twenty-six years? This will need to wait until the next time.

Firstly, I needed to resurrect an old feeding-stand that was in the corner of my garden. I sprayed it up, making it all neat once more, and began the outfitting of the plastic saucer that is a part of the feeding platform. In FIG1, you can see the newly sprayed stand, drying on the table. It was a little rusty on the surface, and I thought that it needed to be given a new lease of life for the camera.

The post’s top image shows the modified saucer, using the plastic surface to create a grip for the puzzles, the Lego studs will help to hold it all in place. With the new puzzles being constructed, once again, from mixed Lego, this will work perfectly. (Are these famous last words?)

Finally, in the images, we can see the feed. I need to begin by feeding the garden, not the actual garden, but the animals within. I have chosen a cheap bag of dried meal-worms (99p), a bag of bird nuts (More expensive nowadays, £5.90), and a starter feeder (£1.99). With a grand total of £8.88, this is not an expensive endeavour. Having the stand already, it has saved another £10 or so. The only other expense will be that of a wildlife camera, I will be purchasing one of these in the next fortnight (£45). (My original idea was to rig a PC camera to an open-source program, but it is a lot less demanding to get one of these inexpensive cameras from eBay. With a couple of weeks of feeding, plus a few extra days of tech-testing, we will be ready to start the experiment by the third week of November.

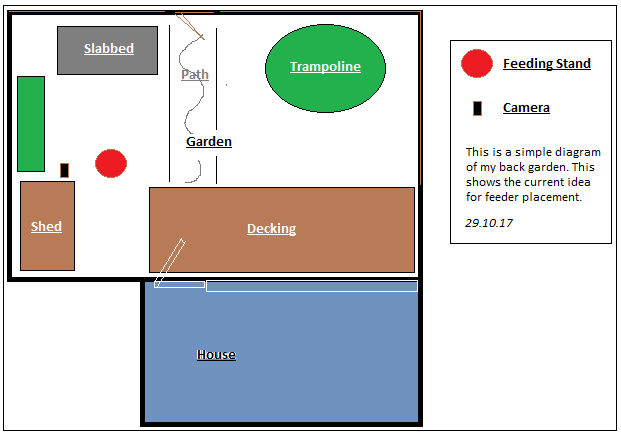

It is important that we consider a few things before starting. The immediate check, is where to position the stand. It can’t be close to a fence, as this could trigger the local cats into thinking there is a new restaurant close by; it also needs to be considerate of the camera. Thought must go into its visibility to thieves, but also give a clear view of the testing space. The image, below, shows the garden outline and the position that has been decided.

By placing it here, it’s not so obvious to the passing public; it is also more than two meters from the closest fence. An extra bonus is the nearby window; this gives a great view of the feeder for live observations. originally, I had decided to put it just ahead of the rear window, but could see that the feeder would be over-exposed.

The other important decisions regard the data collection frequency, recording techniques and their publication. Right now, the idea is to check the video feed (motion-detected) every other day. This will allow for fifteen checks in each month. The experiment shall be conducted through the first half of the winter, leading to completion at the end of January. Each puzzle will be given a maximum of two weeks each. If it is considered to be conclusive, it will allow the experiment to move on. (This may end up shortening the time frame for the investigation, overall.

In another article, I will show puzzle designs, with the first one, built and ready for testing. With the experiment lasting a maximum of nine weeks, there will be a maximum of four puzzles. We might make an adjustment to this timetable as the third or fourth puzzles could be more time consuming, therefore requiring more time to find some data from.

(This project is suitable for primary and secondary Science, Technology, and Mathematical learning. You could easily use Design Technology to produce the puzzles and feeders, therefore including Engineering too!) NOTICE: Please use common sense, always consider the safety of those in your care, first! All prices are from the original wiritng of the post in 2017.